Topeka (Brown v. Board of Education)

Fair warning - this post has a lot of words and almost no images. It is an important subject, though, so I thought it was worthwhile.

Other than being the capitol of the State of Kansas, Topeka’s main claim to fame is as home to Brown vs. Board of Education. The museum, now administered under the NPS , is housed in Monroe Elementary, the school at the center of the controversy.

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racially segregated public facilities were legal, so long as the facilities for black people and white people were equal. The separate but equal doctrine became the de facto law of the land. The ruling constitutionally sanctioned laws barring African-Americans from sharing the same buses, schools and other public facilities as whites; they became known as “Jim Crow” laws. Although the Plessy ruling specifically applied to public transportation within state boundaries, it was generally interpreted as federal approval for segregation in all types of facilities.

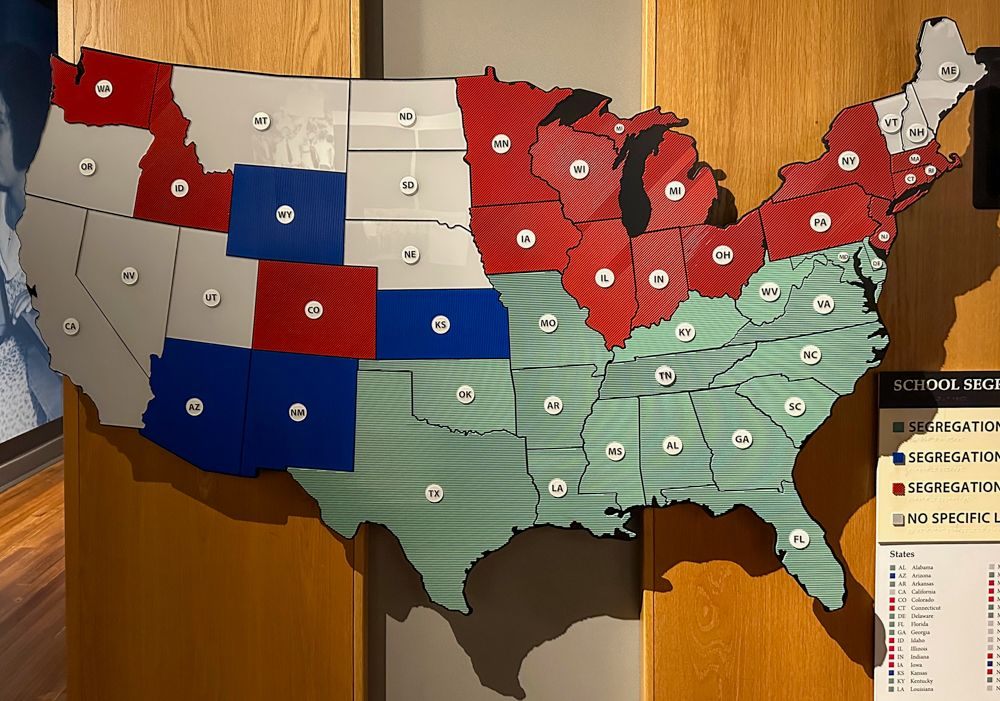

Prior to Brown v. Board , the segregation map of U.S. States looked a lot like the Civil War map. The Southern states required segregated schools, the Northern States generally prohibited it and the territories and Western states had no specific legislation.

It is important to note that segregation and discrimination against people of color frequently included people of Asian, Mexican and Native American descent. In fact, even Southern and Eastern European immigrants (including Jews) and Irish Catholics were initially painted with the same broad brush. However, their skin color allowed them to assimilate more readily once they learned English and American norms and customs.

The Brown case originated in 1951 when the public school system in Topeka, Kansas, refused to enroll local black resident Oliver Brown's daughter at the elementary school closest to their home, instead requiring her to ride a bus to a segregated black school farther away. The Browns and twelve other local black families in similar situations filed a class-action lawsuit in U.S. federal court against the Topeka Board of Education, alleging that its segregation policy was unconstitutional. A special three-judge court of the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas rendered a verdict against the Browns, relying on the precedent of Plessy and its "separate but equal" doctrine. The Browns, represented by NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, then appealed the ruling directly to the Supreme Court.

In fact, the case that the Supreme Court of the U.S. took up comprised five separate cases from around the country, four of which had been denied at the state level. The combined cases were styled Brown v. Board of Education. In what would become a defining moment of his career, Thurgood Marshall, at the time working for the NAACP, led the plaintiff’s team. Other lawyers on the NAACP team included Charles Hamilton Houston, a Harvard educated lawyer who had served as Dean at Howard University, a historically Black university.

The case of Bolling v. Sharp was first brought in Washington D.C. In 1941, a group of parents in Washington, D.C., petitioned the Board of Education of the District of Columbia to open the nearly-completed John Philip Sousa Junior High as an integrated school. The school board denied the petition and the school opened, admitting only whites. At the beginning of the 1950 school year, the parents’ group attempted to enroll eleven African-American students (including the case's plaintiff, Spottswood Bolling), but were refused entry by the school's principal. James Nabrit Jr., a professor of law at Howard University School of Law, a historically black university, filed suit in 1951 on behalf of Bolling and the other students in the District Court for the District of Columbia seeking assistance in the students' admission. After the court dismissed the claim, the case was granted a writ of certiorari by the Supreme Court in 1952. Howard law professor George E. C. Hayes worked with Nabrit on the oral argument for the Supreme Court hearing. The Bolling argument rested on the unconstitutionality of segregation, in contrast to the Brown decision that relied on exposing the fallacy that separate could never be equal.

Because Washington D.C. is effectively a Federal jurisdiction, the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause, which refers only to the states, could not be applied. Rather, the argument held that school segregation was unconstitutional under the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Originally argued in 1952, a year before Brown, Bolling was reargued in 1953, and was unanimously decided in 1954, the same day as Brown.

Davis v. County School Board was the only school segregation case to be initiated by a student protest. The case challenged segregation in Prince Edward County, Virginia. In 1951, two lawyers from the NAACP, Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, filed suit on behalf of 117 students against the school district to integrate the schools. The first plaintiff listed was Dorothy E. Davis, a 14-year old ninth grader, giving title to the case. The lawsuit was unanimously rejected by a three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court. "We have found no hurt or harm to either race," the court ruled. The case was then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court and consolidated with four other cases from other districts around the country into the Brown v. Board of Education case.

The final challenge to segregated schools in Delaware came by way of two separate cases with identical issues. One case developed in the suburb of Claymont and another in the rural community of Hockessin. In both cases attorney Redding directly challenged the issue of segregation. This was done via a lawsuit against the State Board of Education; the Board members were specifically charged, hence the name of the defendant (the first name in the list) in both cases. The resulting cases were called Belton v. Gebhart and Bulah v. Gebhart . This case resulted in a local win. Judge Collin Seitz ruled that the separate but equal doctrine had been violated and that the plaintiffs were entitled to immediate admission to the white school in their communities. Although a victory for the named plaintiffs, the decision did not apply broadly throughout Delaware, hence did not precipitate the sweeping reform they might have hoped for. The Belton and Bulah cases would ultimately join four other NAACP cases in Brown v. Board of Education.

Briggs v. Elliott began in 1948 with a request to afford the same bus transportation to Black children in the community as afforded to White children so that they could attend the same schools. Apparently, they could already attend those schools if they were willing to walk nine or ten miles each way. The initial case, Pearson v. Clarendon County, was dismissed on a technicality when the superintendent noted that the family of the defendant, Levi Pearson, owned a large property covered multiple district lines. The rejection of Pearson v. Clarendon County caused the NAACP attorneys to pivot and raise their target to complete desegregation. In 1949, the NAACP agreed to provide funding and sponsor a case that would go beyond transportation and ask for equal educational opportunities in Clarendon County. A local petition for educational equality was crafted by Rev. Joseph Armstrong DeLaine and Modjeska Monteith Simkins, a noted civil rights worker. In 1952, Briggs v. Elliott , on appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, challenged school segregation in Summerton, South Carolina. As predicted, a three-judge panel found segregation lawful. After a fair amount of legal back and forth, It became the first of the five cases combined into Brown v. Board of Education, and there is a movement to rename the the Supreme Court decision to reflect this.

On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court, in a rare unanimous decision, declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote: We conclude, that in the field of public education the doctrine of ' Separate but Equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. By overturning the legal basis for segregation, the ruling's impact would extend far beyond public schools. However it would be some time before the intention of the Supreme Court would be universally implemented. State and local reaction was slow or defiant. Some schools desegregated immediately; most did not. Arkansas, for example, closed down its entire public school system to avoid desegregation (see the previous post about the Little Rock 9 ). And the Prince Edward County School Board, Virginia, closed its public schools for 5 years in a similar campaign. White children were funded to attend private schools, while Black children were left with no educational facility.

In 1955, the Supreme Court again considered arguments by the schools requesting relief concerning the task of desegregation. In their decision, which became known as Brown II, the court delegated the task of carrying out school desegregation to district courts with orders that desegregation occur "with all deliberate speed.” Unsurprisingly, some factions concentrated on “speed,” while many others focused on “deliberate.”

Brown vs. The Board of Education remains a seminal decision and a turning point in the fight for racial justice and equality. It sparked the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, which resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights act of 1965. I’m sure that many would agree that, although significant strides have been made, universal equality has yet to be achieved and the fight continues world wide.

The other attraction in Topeka is the Evil Knievel Museum. However after my morning with Brown v. Board, I elected to return to my room and spend some time on writing and research. Mr. Knievel just didn’t call to me. Also, I had oped to visit the Kansas History Museum, but like several others, it is temporarily closed for renovation. Too bad.

Topeka itself is a bit sad. The one Main Street contains many boarded up storefronts, and the small downtown quickly gives way to run-down neighborhoods. Rather sad for the Capitol City of Kansas that played such a pivotal role in history. Hopefully a turn-around will happen sooner rather than later. The Hazel Hill Chocolate shop is an encouraging start.

Tomorrow I continue driving westward. My friends Jeff, Onallee and Jillian will join me for a morning of shooting in the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, then I will continue to Manhattan, KS for a one night pit stop.

Other than being the capitol of the State of Kansas, Topeka’s main claim to fame is as home to Brown vs. Board of Education. The museum, now administered under the NPS , is housed in Monroe Elementary, the school at the center of the controversy.

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that racially segregated public facilities were legal, so long as the facilities for black people and white people were equal. The separate but equal doctrine became the de facto law of the land. The ruling constitutionally sanctioned laws barring African-Americans from sharing the same buses, schools and other public facilities as whites; they became known as “Jim Crow” laws. Although the Plessy ruling specifically applied to public transportation within state boundaries, it was generally interpreted as federal approval for segregation in all types of facilities.

Prior to Brown v. Board , the segregation map of U.S. States looked a lot like the Civil War map. The Southern states required segregated schools, the Northern States generally prohibited it and the territories and Western states had no specific legislation.

It is important to note that segregation and discrimination against people of color frequently included people of Asian, Mexican and Native American descent. In fact, even Southern and Eastern European immigrants (including Jews) and Irish Catholics were initially painted with the same broad brush. However, their skin color allowed them to assimilate more readily once they learned English and American norms and customs.

The Brown case originated in 1951 when the public school system in Topeka, Kansas, refused to enroll local black resident Oliver Brown's daughter at the elementary school closest to their home, instead requiring her to ride a bus to a segregated black school farther away. The Browns and twelve other local black families in similar situations filed a class-action lawsuit in U.S. federal court against the Topeka Board of Education, alleging that its segregation policy was unconstitutional. A special three-judge court of the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas rendered a verdict against the Browns, relying on the precedent of Plessy and its "separate but equal" doctrine. The Browns, represented by NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, then appealed the ruling directly to the Supreme Court.

In fact, the case that the Supreme Court of the U.S. took up comprised five separate cases from around the country, four of which had been denied at the state level. The combined cases were styled Brown v. Board of Education. In what would become a defining moment of his career, Thurgood Marshall, at the time working for the NAACP, led the plaintiff’s team. Other lawyers on the NAACP team included Charles Hamilton Houston, a Harvard educated lawyer who had served as Dean at Howard University, a historically Black university.

The case of Bolling v. Sharp was first brought in Washington D.C. In 1941, a group of parents in Washington, D.C., petitioned the Board of Education of the District of Columbia to open the nearly-completed John Philip Sousa Junior High as an integrated school. The school board denied the petition and the school opened, admitting only whites. At the beginning of the 1950 school year, the parents’ group attempted to enroll eleven African-American students (including the case's plaintiff, Spottswood Bolling), but were refused entry by the school's principal. James Nabrit Jr., a professor of law at Howard University School of Law, a historically black university, filed suit in 1951 on behalf of Bolling and the other students in the District Court for the District of Columbia seeking assistance in the students' admission. After the court dismissed the claim, the case was granted a writ of certiorari by the Supreme Court in 1952. Howard law professor George E. C. Hayes worked with Nabrit on the oral argument for the Supreme Court hearing. The Bolling argument rested on the unconstitutionality of segregation, in contrast to the Brown decision that relied on exposing the fallacy that separate could never be equal.

Because Washington D.C. is effectively a Federal jurisdiction, the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause, which refers only to the states, could not be applied. Rather, the argument held that school segregation was unconstitutional under the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Originally argued in 1952, a year before Brown, Bolling was reargued in 1953, and was unanimously decided in 1954, the same day as Brown.

Davis v. County School Board was the only school segregation case to be initiated by a student protest. The case challenged segregation in Prince Edward County, Virginia. In 1951, two lawyers from the NAACP, Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, filed suit on behalf of 117 students against the school district to integrate the schools. The first plaintiff listed was Dorothy E. Davis, a 14-year old ninth grader, giving title to the case. The lawsuit was unanimously rejected by a three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court. "We have found no hurt or harm to either race," the court ruled. The case was then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court and consolidated with four other cases from other districts around the country into the Brown v. Board of Education case.

The final challenge to segregated schools in Delaware came by way of two separate cases with identical issues. One case developed in the suburb of Claymont and another in the rural community of Hockessin. In both cases attorney Redding directly challenged the issue of segregation. This was done via a lawsuit against the State Board of Education; the Board members were specifically charged, hence the name of the defendant (the first name in the list) in both cases. The resulting cases were called Belton v. Gebhart and Bulah v. Gebhart . This case resulted in a local win. Judge Collin Seitz ruled that the separate but equal doctrine had been violated and that the plaintiffs were entitled to immediate admission to the white school in their communities. Although a victory for the named plaintiffs, the decision did not apply broadly throughout Delaware, hence did not precipitate the sweeping reform they might have hoped for. The Belton and Bulah cases would ultimately join four other NAACP cases in Brown v. Board of Education.

Briggs v. Elliott began in 1948 with a request to afford the same bus transportation to Black children in the community as afforded to White children so that they could attend the same schools. Apparently, they could already attend those schools if they were willing to walk nine or ten miles each way. The initial case, Pearson v. Clarendon County, was dismissed on a technicality when the superintendent noted that the family of the defendant, Levi Pearson, owned a large property covered multiple district lines. The rejection of Pearson v. Clarendon County caused the NAACP attorneys to pivot and raise their target to complete desegregation. In 1949, the NAACP agreed to provide funding and sponsor a case that would go beyond transportation and ask for equal educational opportunities in Clarendon County. A local petition for educational equality was crafted by Rev. Joseph Armstrong DeLaine and Modjeska Monteith Simkins, a noted civil rights worker. In 1952, Briggs v. Elliott , on appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, challenged school segregation in Summerton, South Carolina. As predicted, a three-judge panel found segregation lawful. After a fair amount of legal back and forth, It became the first of the five cases combined into Brown v. Board of Education, and there is a movement to rename the the Supreme Court decision to reflect this.

On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court, in a rare unanimous decision, declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote: We conclude, that in the field of public education the doctrine of ' Separate but Equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. By overturning the legal basis for segregation, the ruling's impact would extend far beyond public schools. However it would be some time before the intention of the Supreme Court would be universally implemented. State and local reaction was slow or defiant. Some schools desegregated immediately; most did not. Arkansas, for example, closed down its entire public school system to avoid desegregation (see the previous post about the Little Rock 9 ). And the Prince Edward County School Board, Virginia, closed its public schools for 5 years in a similar campaign. White children were funded to attend private schools, while Black children were left with no educational facility.

In 1955, the Supreme Court again considered arguments by the schools requesting relief concerning the task of desegregation. In their decision, which became known as Brown II, the court delegated the task of carrying out school desegregation to district courts with orders that desegregation occur "with all deliberate speed.” Unsurprisingly, some factions concentrated on “speed,” while many others focused on “deliberate.”

Brown vs. The Board of Education remains a seminal decision and a turning point in the fight for racial justice and equality. It sparked the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, which resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights act of 1965. I’m sure that many would agree that, although significant strides have been made, universal equality has yet to be achieved and the fight continues world wide.

The other attraction in Topeka is the Evil Knievel Museum. However after my morning with Brown v. Board, I elected to return to my room and spend some time on writing and research. Mr. Knievel just didn’t call to me. Also, I had oped to visit the Kansas History Museum, but like several others, it is temporarily closed for renovation. Too bad.

Topeka itself is a bit sad. The one Main Street contains many boarded up storefronts, and the small downtown quickly gives way to run-down neighborhoods. Rather sad for the Capitol City of Kansas that played such a pivotal role in history. Hopefully a turn-around will happen sooner rather than later. The Hazel Hill Chocolate shop is an encouraging start.

Tomorrow I continue driving westward. My friends Jeff, Onallee and Jillian will join me for a morning of shooting in the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, then I will continue to Manhattan, KS for a one night pit stop.

61 photo galleries

50 States

- Big Sur

- Salinas

- Laguna Beach

- San Diego

- California

- Grand Canyon

- Sedona

- Utah

- Syracuse

- Moab

- Denver

- Manitou Springs

- Calhan

- Mesa Verde

- Los Alamos

- Santa Fe

- Carlsbad

- New Mexico

- Eureka Springs

- Little Rock

- Birmingham

- Jackson

- Lottie

- Ten Thousand Islands

- Jerome

- Savannah

- White

- Asheville

- Sandstone Falls

- Baltimore

- Timonium

- Maryland

- Berlin

- Milton

- Smyrna

- Ocean City

- Detroit

- Upper Peninsula of Michigan

- Michigan

- Herod

- Ozark

- Two Harbors

- Carlton

- Madison County

- Oakley

- Valentine

- South Dakota

- United States

- Yellowstone National Park

- Lima

- Idaho

- Port Townsend

- Lincoln City

- Newport

- San Francisco