Providence 2

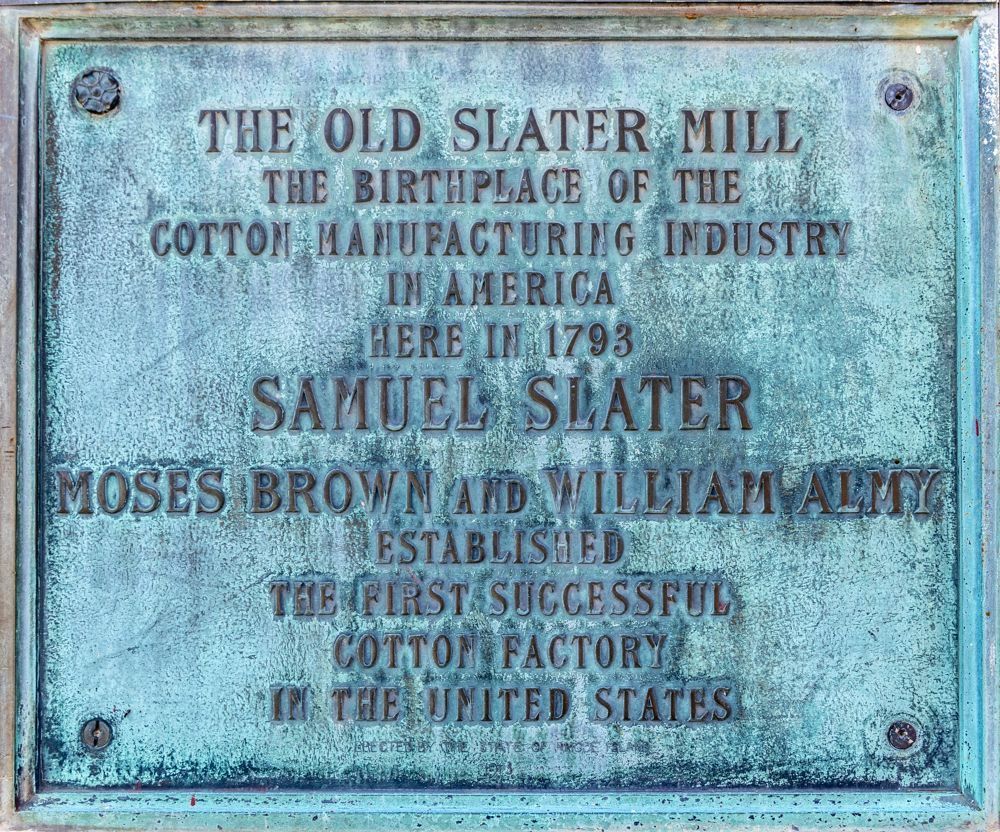

Today I drove over to Slater Mill, the first “successful” cotton mill in the U.S. There had apparently been some false starts prior to this one. As mentioned yesterday, the Blackstone River valley was ideal for manufacturing because power could be generated from the river. From its origin in Worcester, MA, it dropped somewhere between 400-600 feet in elevation (depending on the source of the information), with multiple falls that could harnessed by building dams.

Industry of another kind had already begun just adjacent to the Slater Mill site. Iron forging was already taking advantage of the power inherent in the river, although a dam, per se, had not been built. Although friction would ensue between the owners of each plant based on water power rights, the manufacturing skills themselves would prove critical to the textile milling industry to make the required machinery.

Moses Brown and William Almy had already built a prospective mill on this site, however they were having trouble getting their machines to work properly. Samual Slater had worked at a cotton mill in England and was well versed in the whole process. He had come to the U.S. seeing to own rather than work in a mill. He offered his services to Brown and Almy, and within a couple of years they had built a dam and had the plant up and running. The dam was what caused the friction with the existing iron forge just downstream and resulted in ongoing lawsuits. Ultimately, the cotton mill survived, the forge did not.

The cotton itself was brought in from both Caribbean plantations and Southern plantations, both by ship. The location of Slater mill at the mouth of the river was another factor in its success as the product could be offloaded near to where it was to be used. Of course both sources of cotton were produced by enslaved persons who worked under horrendous conditions. Interestingly, enslaved persons did not work at the mill itself.

At the mill, initially only children were employed. Their small fingers were idea for picking debris out of cotton fibers. Again, the conditions were terrible. The noise from the spinners, other machinery and even the falls just outside was deafening, leading to hearing loss. The cotton fibers in the air were inhaled, causing breathing problems. The floor was slippery due to an accumulation of cotton fibers. And even just handling the cotton on a daily basis caused dry cracked skin. As well, many windows let in light, but they were kept closed to increase the humidity. This was good for the cotton, but the heat and humidity generated in the sealed building also contributed to difficult and dangerous working conditions.

You might ask why anyone would choose to work in such conditions? The simple answer was that they were paid in cash for hours worked rather than amount of product (as on a plantation). The 12 hour days were likely longer as initially no clock was available on the premise. Eventually even more desperate people were hired - widows and orphans - allowing the mill to slash pay and increase hours. By 1824, some young woman had been hired to work on the mill floor. Men, of course had always worked at building and maintaining the machinery, also of course at a higher pay scale. The young women became so angry at the increasingly deteriorating conditions that, in 1824, they organized the first industrial labor strike in American history. This was before the ITU had been formed to protect the workers. It is not known what was the final agreement, but the strike was settled and the women returned to work. It is known that a clock was installed next to the bell that was used to announce the beginning and end of the workday.

Slater was made a partner by Brown and Almy and, by the time the mill closed in 1895, he was worth 2 million dollars, representing enormous wealth at the time.

After a short break, I walked over Federal Hill, also known as Little Italy. Everyone I spoke to insisted that I visit this area. It did seem to be mostly about the restaurants - mostly Italian, but also a smattering of other cuisines. Scungilli seems to be a specialty particular to Rhode Island. Scungilli is often translated as snails, but it is actually Whelk, a kind of shellfish similar to a Conch. They are sometimes called sea snails, hence the confusion. The meat is coarsely chopped and made into a salad. I found the dish at Andinos , a classic low-key Italian eatery with photos of Italian singers, actors and athletes line the walls. I enjoyed it and took most of the very large portion back with me where it will supply several more meals.

With that my week in Rhode Island concludes. Tomorrow I drive north to Massachusetts.

Industry of another kind had already begun just adjacent to the Slater Mill site. Iron forging was already taking advantage of the power inherent in the river, although a dam, per se, had not been built. Although friction would ensue between the owners of each plant based on water power rights, the manufacturing skills themselves would prove critical to the textile milling industry to make the required machinery.

Moses Brown and William Almy had already built a prospective mill on this site, however they were having trouble getting their machines to work properly. Samual Slater had worked at a cotton mill in England and was well versed in the whole process. He had come to the U.S. seeing to own rather than work in a mill. He offered his services to Brown and Almy, and within a couple of years they had built a dam and had the plant up and running. The dam was what caused the friction with the existing iron forge just downstream and resulted in ongoing lawsuits. Ultimately, the cotton mill survived, the forge did not.

The cotton itself was brought in from both Caribbean plantations and Southern plantations, both by ship. The location of Slater mill at the mouth of the river was another factor in its success as the product could be offloaded near to where it was to be used. Of course both sources of cotton were produced by enslaved persons who worked under horrendous conditions. Interestingly, enslaved persons did not work at the mill itself.

At the mill, initially only children were employed. Their small fingers were idea for picking debris out of cotton fibers. Again, the conditions were terrible. The noise from the spinners, other machinery and even the falls just outside was deafening, leading to hearing loss. The cotton fibers in the air were inhaled, causing breathing problems. The floor was slippery due to an accumulation of cotton fibers. And even just handling the cotton on a daily basis caused dry cracked skin. As well, many windows let in light, but they were kept closed to increase the humidity. This was good for the cotton, but the heat and humidity generated in the sealed building also contributed to difficult and dangerous working conditions.

You might ask why anyone would choose to work in such conditions? The simple answer was that they were paid in cash for hours worked rather than amount of product (as on a plantation). The 12 hour days were likely longer as initially no clock was available on the premise. Eventually even more desperate people were hired - widows and orphans - allowing the mill to slash pay and increase hours. By 1824, some young woman had been hired to work on the mill floor. Men, of course had always worked at building and maintaining the machinery, also of course at a higher pay scale. The young women became so angry at the increasingly deteriorating conditions that, in 1824, they organized the first industrial labor strike in American history. This was before the ITU had been formed to protect the workers. It is not known what was the final agreement, but the strike was settled and the women returned to work. It is known that a clock was installed next to the bell that was used to announce the beginning and end of the workday.

Slater was made a partner by Brown and Almy and, by the time the mill closed in 1895, he was worth 2 million dollars, representing enormous wealth at the time.

After a short break, I walked over Federal Hill, also known as Little Italy. Everyone I spoke to insisted that I visit this area. It did seem to be mostly about the restaurants - mostly Italian, but also a smattering of other cuisines. Scungilli seems to be a specialty particular to Rhode Island. Scungilli is often translated as snails, but it is actually Whelk, a kind of shellfish similar to a Conch. They are sometimes called sea snails, hence the confusion. The meat is coarsely chopped and made into a salad. I found the dish at Andinos , a classic low-key Italian eatery with photos of Italian singers, actors and athletes line the walls. I enjoyed it and took most of the very large portion back with me where it will supply several more meals.

With that my week in Rhode Island concludes. Tomorrow I drive north to Massachusetts.

61 photo galleries

50 States

- Big Sur

- Salinas

- Laguna Beach

- San Diego

- California

- Grand Canyon

- Sedona

- Utah

- Syracuse

- Moab

- Denver

- Manitou Springs

- Calhan

- Mesa Verde

- Los Alamos

- Santa Fe

- Carlsbad

- New Mexico

- Eureka Springs

- Little Rock

- Birmingham

- Jackson

- Lottie

- Ten Thousand Islands

- Jerome

- Savannah

- White

- Asheville

- Sandstone Falls

- Baltimore

- Timonium

- Maryland

- Berlin

- Milton

- Smyrna

- Ocean City

- Detroit

- Upper Peninsula of Michigan

- Michigan

- Herod

- Ozark

- Two Harbors

- Carlton

- Madison County

- Oakley

- Valentine

- South Dakota

- United States

- Yellowstone National Park

- Lima

- Idaho

- Port Townsend

- Lincoln City

- Newport

- San Francisco