Natick ([Salem]

This morning I drove up to the NorthEastern corner of Massachusetts to visit Salem. This area was, of course, the site of the infamous Salem Witch Trials , but it has other attractions to offer as well. I first wasted some time figuring out parking. I could find very little information on any website about available parking. I started out in a pay lot a few blocks out of town; it was only a dollar an hour, but there was a 4 hour limit. Once the Salem Armory Visitor Center opened at 10 AM, I was able to find out that the garage across the street did offer all-day parking, but filled up early. I made what turned out to be the smart decision to forfeit most of my four bucks and move my car immediately. The garage was already almost full and did fill up later in the day. However, for an additional $7.50 I was able to find a covered spot out of the blazing sun and in the center of town.

Next, I considered whether I wanted to try to take one of the trolley tours . It was unnecessary for distance - the town is small and very walkable - but I was interested because of the history that supposedly would be provided. After taking one look at the crowds, I decided to skip it.

Instead, I walked over to the Charter Street Cemetery . Although the on-site docent mentioned that this was the second oldest cemetery in the U.S., most web sites list it as the oldest. It was established in 1637, and its most infamous inhabitant is Judge John Hawthorn, who prosecuted 20 women and men who were sentenced to death for crimes of witchcraft that they did not commit. Images on the headstones showed the evolution of Puritan funerary art from death’s head to soul effigies to urns and willows. Immediately adjacent to the cemetery is a memorial to the innocent men and women who were executed (most hanged, one man pressed to death) as a result of the tragic farce that was the Salem Witch Trials.

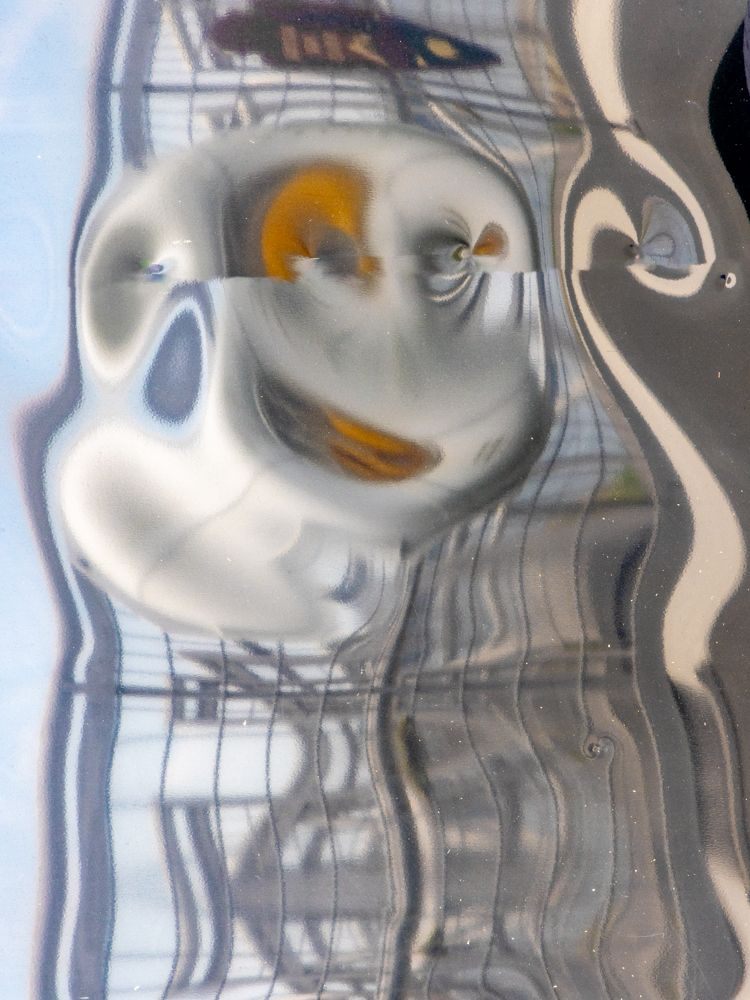

By then, it was time to report for my timed entry to the Salem Witch museum . Although this looked like the best of the lot, it turned out to be a waste of time and money. Most of the experience was a show, which spotlighted various life-sized dioramas and was narrated by a dramatic disembodied voice. It contained historical inaccuracies (as did some of the exhibits) and was mostly just annoying. The secondary room was slightly better, giving a timeline of persecutions for witchcraft through history and some modern-day parallels. Still, my time would have been spent better elsewhere.

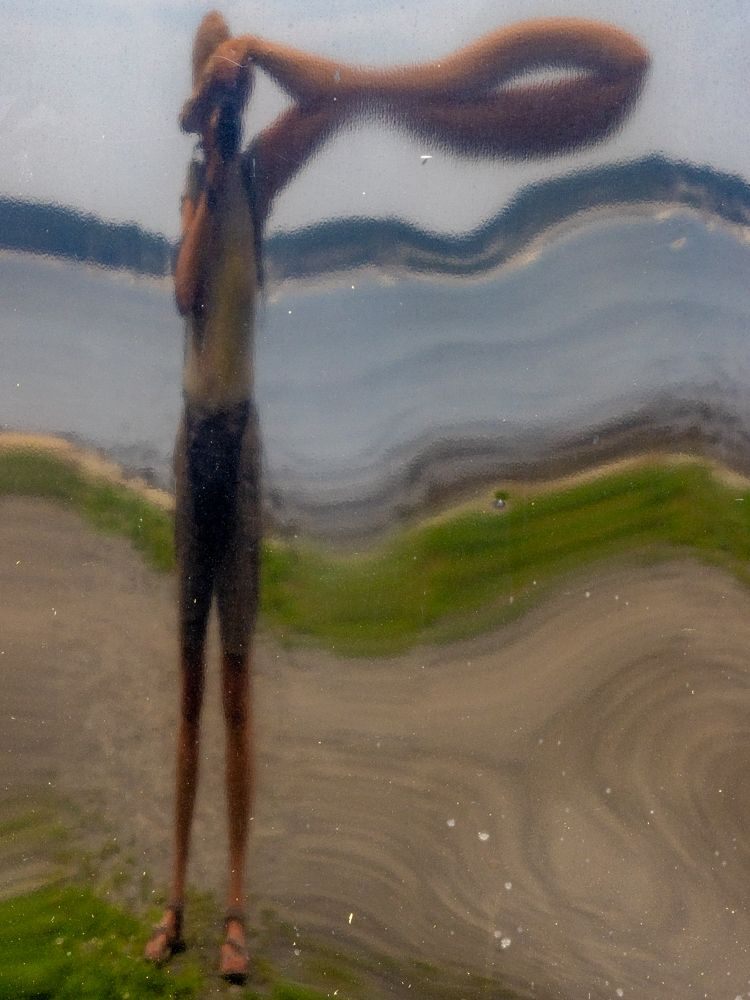

After grabbing some lunch at Red’s Sandwich Shop , I stopped at the Peabody Essex Museum . I had seen an exhibition advertised, “As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic ” that looked intriguing. This turned out to be well worthwhile and a nice escape from commercial witch madness, which simply pervades the city. PEM is one of the oldest museums in the country, dating back to 1799 when captains in the East India Marine Society returned with exotic artifacts from long ocean voyages. In its current iteration, it is a world-class art museum.

I then walked over to the Salem Maritime National Historic Site which comprises 9 acres of land and 12 historic structures along the waterfront. It was established in 1938 as the first National Historic Site in the United States. While it encompasses a lot of history, it is not visually that interesting.

I walked back to the Armory Visitor Center to catch a film they had mentioned - "Salem Witch Hunt: Examine the Evidence " - that sets forth the latest academic research about the the generation of the hysteria that led to the Salem Witch Trials. This was a far more objective and scientific treatment of the subject matter. I’m not sure why it was not more widely advertised - I only knew of it because the ranger at the Visitor’s center mentioned it when I went in to ask about parking. I think there were all of five of us in a theatre with a capacity to seat hundreds. The information presented in the documentary is also found in a recent Smithsonian Magazine article, A Brief History of the Salem Witch Trials .

The mythology surrounding the Salem Witch Trials is legend. And some of it turns out actually to be mythology. For example, I had always learned that one explanation for the erratic behavior of the “possessed” children was Ergot poisoning , due to the Ergot fungus which grows on rye, which was one of the staple grains of the villagers. Although this theory is still perpetuated in museums in Salem, and on the internet, it was not even discussed in the movie. Indeed, if this was a reasonable culprit, why did not all of the townspeople exhibit the concerning symptoms, not just young girls.

The documentary proposes a more supportable explanation of the confluence of religious extremism and social tensions that led to mass hysteria. At the time, two separate communities existed in the area, Salem Town, a relatively wealthy community of seafarers and merchants who lived near the coast, and Salem Village, a poorer farming community located inland. Around 1689, refugees from King William’s war began to descend on Salem Village, straining an already precarious economy. They also were not of the strict Puritan persuasion that led this group to escape the Church in England in the first place. Controversy also brewed over the Reverend Samuel Parris, who became Salem Village’s first ordained minister in 1689 and quickly gained a reputation for his rigid ways and greedy nature. He was brought in to help unify the community and only succeeding in further dividing it.

In the medieval and early modern eras, many religions, including Christianity, taught that the devil could give people known as witches the power to harm others in return for their loyalty. It can only be suspicious that Parris’ 9-year-old daughter Elizabeth and 11-year-old niece, Abigail Williams were the first to exhibit “symptoms” of apparent madness - supposed convulsions, contortions, uncontrollable movements and guttural sounds. After a third girl, 12-year-old Ann Putnam Jr. also began acting strangely, civil authorities decided to get to the bottom of the matter. Under pressure from magistrates John Hawthorne and Jonathan Corwin, the girls blamed three women for afflicting them: Tituba, a Caribbean woman enslaved by the Parris family; Sarah Good, a homeless beggar; and Sarah Osborne, an elderly impoverished woman. As usual, these collateral victims represented the downtrodden and ill-resourced members of society, easily blamed and unable to defend themselves.

Osborne and Good claimed innocence, but Tituba provided a false confession. With the seeds of paranoia planted, a stream of accusations followed over the next few months. Amongst the evidence presented in court was “spectral evidence” - testimony about dreams and visions. Respected minister Cotton Mather implored the court to preclude such evidence, a plea in which he was joined by his son Increase Mather, then-president of Harvard. Increase proclaimed that “It were better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person be condemned,” a concept still quoted today. Only after Governor Phips’ own wife was questioned as a suspected witch, was spectral evidence disallowed, the special court of Oyer (to hear) and Terminer (to decide) dissolved, and the trials commended to the Superior Court of Judicature, which condemned just 3 of 56 defendants. Interestingly, perhaps because she “confessed,” Tituba was imprisoned, but not executed and was eventually released.

By May 1693, Governor Phips had pardoned all those imprisoned on witchcraft charges. But that would not bring back the nineteen men and women who had been hanged on Gallows Hill and one man, who was pressed to death after refusing to submit himself to a trial. At least five of the accused died in jail. While the trials were eventually declared unlawful and some restitution was paid to heirs, it wasn’t until 1957—more than 250 years later—that Massachusetts formally apologized for the travesty that occurred in 1692. Elizabeth Johnson, was was left out of the 1957 resolution for reasons unknown but received an official pardon in 2022 after a successful lobbying campaign by a class of eighth-grade civics students.

Many similar examples of hysterical persecution exist throughout human history: Persecution of supposed Communists (McCarthyism), persecution of Jews, Gypsies and other ethnic minorities (the Holocaust), persecution of various races (based solely on unfounded fear) persecution of LGTBQ+ people by right-wing religious extremists (especially during the height of the AIDs epidemic) - the list goes on and on. A relatively modern example, which bears an eerie resemblance to the Salem Witch Trials occurred in Kern County , CA. Many parents, relatives and caregivers were falsely prosecuted and convicted of molesting and performing satanic ritualistic abuse on scores of children. The prosecution was led by corrupt DA Ed Jagels, and the evidence relied on coerced confessions of young children. The story is related in a documentary narrated by Sean Penn, appropriately entitled “Witch Hunt .” Eventually the convictions were all overturned, but not until innocent people served time in prison and families were torn apart.

Tomorrow’s plans are as yet uncertain. As always, stay tuned.

Next, I considered whether I wanted to try to take one of the trolley tours . It was unnecessary for distance - the town is small and very walkable - but I was interested because of the history that supposedly would be provided. After taking one look at the crowds, I decided to skip it.

Instead, I walked over to the Charter Street Cemetery . Although the on-site docent mentioned that this was the second oldest cemetery in the U.S., most web sites list it as the oldest. It was established in 1637, and its most infamous inhabitant is Judge John Hawthorn, who prosecuted 20 women and men who were sentenced to death for crimes of witchcraft that they did not commit. Images on the headstones showed the evolution of Puritan funerary art from death’s head to soul effigies to urns and willows. Immediately adjacent to the cemetery is a memorial to the innocent men and women who were executed (most hanged, one man pressed to death) as a result of the tragic farce that was the Salem Witch Trials.

By then, it was time to report for my timed entry to the Salem Witch museum . Although this looked like the best of the lot, it turned out to be a waste of time and money. Most of the experience was a show, which spotlighted various life-sized dioramas and was narrated by a dramatic disembodied voice. It contained historical inaccuracies (as did some of the exhibits) and was mostly just annoying. The secondary room was slightly better, giving a timeline of persecutions for witchcraft through history and some modern-day parallels. Still, my time would have been spent better elsewhere.

After grabbing some lunch at Red’s Sandwich Shop , I stopped at the Peabody Essex Museum . I had seen an exhibition advertised, “As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic ” that looked intriguing. This turned out to be well worthwhile and a nice escape from commercial witch madness, which simply pervades the city. PEM is one of the oldest museums in the country, dating back to 1799 when captains in the East India Marine Society returned with exotic artifacts from long ocean voyages. In its current iteration, it is a world-class art museum.

I then walked over to the Salem Maritime National Historic Site which comprises 9 acres of land and 12 historic structures along the waterfront. It was established in 1938 as the first National Historic Site in the United States. While it encompasses a lot of history, it is not visually that interesting.

I walked back to the Armory Visitor Center to catch a film they had mentioned - "Salem Witch Hunt: Examine the Evidence " - that sets forth the latest academic research about the the generation of the hysteria that led to the Salem Witch Trials. This was a far more objective and scientific treatment of the subject matter. I’m not sure why it was not more widely advertised - I only knew of it because the ranger at the Visitor’s center mentioned it when I went in to ask about parking. I think there were all of five of us in a theatre with a capacity to seat hundreds. The information presented in the documentary is also found in a recent Smithsonian Magazine article, A Brief History of the Salem Witch Trials .

The mythology surrounding the Salem Witch Trials is legend. And some of it turns out actually to be mythology. For example, I had always learned that one explanation for the erratic behavior of the “possessed” children was Ergot poisoning , due to the Ergot fungus which grows on rye, which was one of the staple grains of the villagers. Although this theory is still perpetuated in museums in Salem, and on the internet, it was not even discussed in the movie. Indeed, if this was a reasonable culprit, why did not all of the townspeople exhibit the concerning symptoms, not just young girls.

The documentary proposes a more supportable explanation of the confluence of religious extremism and social tensions that led to mass hysteria. At the time, two separate communities existed in the area, Salem Town, a relatively wealthy community of seafarers and merchants who lived near the coast, and Salem Village, a poorer farming community located inland. Around 1689, refugees from King William’s war began to descend on Salem Village, straining an already precarious economy. They also were not of the strict Puritan persuasion that led this group to escape the Church in England in the first place. Controversy also brewed over the Reverend Samuel Parris, who became Salem Village’s first ordained minister in 1689 and quickly gained a reputation for his rigid ways and greedy nature. He was brought in to help unify the community and only succeeding in further dividing it.

In the medieval and early modern eras, many religions, including Christianity, taught that the devil could give people known as witches the power to harm others in return for their loyalty. It can only be suspicious that Parris’ 9-year-old daughter Elizabeth and 11-year-old niece, Abigail Williams were the first to exhibit “symptoms” of apparent madness - supposed convulsions, contortions, uncontrollable movements and guttural sounds. After a third girl, 12-year-old Ann Putnam Jr. also began acting strangely, civil authorities decided to get to the bottom of the matter. Under pressure from magistrates John Hawthorne and Jonathan Corwin, the girls blamed three women for afflicting them: Tituba, a Caribbean woman enslaved by the Parris family; Sarah Good, a homeless beggar; and Sarah Osborne, an elderly impoverished woman. As usual, these collateral victims represented the downtrodden and ill-resourced members of society, easily blamed and unable to defend themselves.

Osborne and Good claimed innocence, but Tituba provided a false confession. With the seeds of paranoia planted, a stream of accusations followed over the next few months. Amongst the evidence presented in court was “spectral evidence” - testimony about dreams and visions. Respected minister Cotton Mather implored the court to preclude such evidence, a plea in which he was joined by his son Increase Mather, then-president of Harvard. Increase proclaimed that “It were better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person be condemned,” a concept still quoted today. Only after Governor Phips’ own wife was questioned as a suspected witch, was spectral evidence disallowed, the special court of Oyer (to hear) and Terminer (to decide) dissolved, and the trials commended to the Superior Court of Judicature, which condemned just 3 of 56 defendants. Interestingly, perhaps because she “confessed,” Tituba was imprisoned, but not executed and was eventually released.

By May 1693, Governor Phips had pardoned all those imprisoned on witchcraft charges. But that would not bring back the nineteen men and women who had been hanged on Gallows Hill and one man, who was pressed to death after refusing to submit himself to a trial. At least five of the accused died in jail. While the trials were eventually declared unlawful and some restitution was paid to heirs, it wasn’t until 1957—more than 250 years later—that Massachusetts formally apologized for the travesty that occurred in 1692. Elizabeth Johnson, was was left out of the 1957 resolution for reasons unknown but received an official pardon in 2022 after a successful lobbying campaign by a class of eighth-grade civics students.

Many similar examples of hysterical persecution exist throughout human history: Persecution of supposed Communists (McCarthyism), persecution of Jews, Gypsies and other ethnic minorities (the Holocaust), persecution of various races (based solely on unfounded fear) persecution of LGTBQ+ people by right-wing religious extremists (especially during the height of the AIDs epidemic) - the list goes on and on. A relatively modern example, which bears an eerie resemblance to the Salem Witch Trials occurred in Kern County , CA. Many parents, relatives and caregivers were falsely prosecuted and convicted of molesting and performing satanic ritualistic abuse on scores of children. The prosecution was led by corrupt DA Ed Jagels, and the evidence relied on coerced confessions of young children. The story is related in a documentary narrated by Sean Penn, appropriately entitled “Witch Hunt .” Eventually the convictions were all overturned, but not until innocent people served time in prison and families were torn apart.

Tomorrow’s plans are as yet uncertain. As always, stay tuned.

61 photo galleries

50 States

- Big Sur

- Salinas

- Laguna Beach

- San Diego

- California

- Grand Canyon

- Sedona

- Utah

- Syracuse

- Moab

- Denver

- Manitou Springs

- Calhan

- Mesa Verde

- Los Alamos

- Santa Fe

- Carlsbad

- New Mexico

- Eureka Springs

- Little Rock

- Birmingham

- Jackson

- Lottie

- Ten Thousand Islands

- Jerome

- Savannah

- White

- Asheville

- Sandstone Falls

- Baltimore

- Timonium

- Maryland

- Berlin

- Milton

- Smyrna

- Ocean City

- Detroit

- Upper Peninsula of Michigan

- Michigan

- Herod

- Ozark

- Two Harbors

- Carlton

- Madison County

- Oakley

- Valentine

- South Dakota

- United States

- Yellowstone National Park

- Lima

- Idaho

- Port Townsend

- Lincoln City

- Newport

- San Francisco